Rare engine explosion could have been disaster

Sunday, June 4, 2000

THE RECORD

|

By DOUG MOST

Staff Writer

Continental Airlines Flight 60 was barreling smoothly down

the runway at Newark International Airport, a DC-10 carrying 234 passengers

and crew members on a trans-Atlantic flight. At close to 200 mph, with

its wheels just about to lift from the tarmac, there was an explosion under

the left wing.

Passengers on the April 25 flight to Brussels, Belgium, felt the

jolt and were no doubt aware it meant something was wrong. But for veteran

Capt. Doug Schull, his crew, and air-traffic controllers, it marked just

the beginning of 34 nail-biting minutes, as they rushed to dump 90,000

pounds of fuel just 3,000 feet over North Jersey and clear out airspace

to get the plane back on the ground as quickly as possible without a catastrophe.

The troubled aircraft landed safely, and its problems are now

the subject of an investigation by the National Transportation Safety Board.

For reasons that are still unclear, the left-wing engine -- one

of three on the jumbo jet -- had suffered what's known in aviation terms

as an "uncontained engine failure," meaning parts and fragments fly out

of the engine. Such an event is rare -- it has happened only 20 times since

1995 out of some 300 million flights. But in several of those incidents,

pieces such as fan blades penetrated the cabin like bullets. Only luck

prevented that from happening with Flight 60.

"This one didn't sound good right from the start," said Mike Reilly,

the air-traffic controller who handled the plane on takeoff. "You saw smoke,

and you saw he wasn't climbing well. He was really straining to get up

in the air."

Reilly, and others familiar with the incident, praised the flight

crew's handling of a heavy plane that was struggling to fly and difficult

to land. Aviation experts said the troubles that brought the Continental

plane down for an emergency landing at 8:16 p.m. appear frighteningly similar

to those of two other flights that culminated less fortunately after uncontained

engine failures:

United Airlines Flight 232 on July 19, 1989, ended with the DC-10

cartwheeling on the runway during an emergency landing in Sioux City, Iowa,

killing 110 people.

Delta Flight 1288 on July 6, 1996, suffered an engine failure

during takeoff in Pensacola, Fla. Parts were hurled into the left side

of the cabin, killing two passengers.

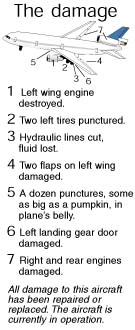

Continental Flight 60 dropped one piece in flight onto a rooftop

in Moonachie and had a hodgepodge of problems when it came to a stop on

the runway. A hunk of engine casing the size of a desktop dropped off on

the tarmac. All three engines and all of the brakes were damaged and ultimately

had to be replaced. Two tires were blown. A dozen puncture holes, some

the size of pumpkins, were ripped in the cargo hold and the left wing flaps.

The left panel door that protects the landing gear was damaged. Hydraulic

lines to the brakes were severed, and fluid sprayed around the wheel wells.

"This plane was in serious trouble," said J.P. Tristani of Ramsey,

a retired Eastern Airlines pilot and aeronautical engineer who studied

the detailed preliminary report on the incident. "This plane was five minutes

away from being a glider heading into Newark."

Such near disasters in the skies are typically reported in the

media, but Continental Flight 60 received only brief mention, and only

because of the engine part that landed in Moonachie.

At the time, Continental officials played down the incident, saying

only that the plane blew a tire and an indicator light came on, forcing

the pilot to return to Newark.

But a blown tire and indicator light were the least of the DC-10's

problems.

NTSB investigator Paul Cox said he would not comment until he

has all the facts about Flight 60.

But experts said the most likely causes could include anything

from a bird being sucked into an engine, to a mechanical failure inside

the left-wing engine, to a human error related to the maintenance of the

aircraft.

"It just looks like an unusual event," Continental spokeswoman

Catherine Stengel said last week. "We're thankful the training of our crew

allowed them to handle an uncommon situation, and air-traffic control did

a superb job of guiding it back."

She said the plane was repaired and put back into service. "We

took it on a test flight, and it did fine," Stengel said.

Preliminary reports, documents obtained by The Record, and expert

analysis provide a vivid account of just how much Flight 60 struggled from

the moment of its takeoff to its unscheduled landing back at Newark on

April 25.

THE RECORD

|

The Flight

Under clear skies at 7:42 p.m., the McDonnell-Douglas DC-10-30,

which made its first flight on Jan. 21, 1973 for Alitalia, pulled onto

Runway 4-L at Newark, which points north, toward Bergen County. The flight

was an hour behind schedule, not uncommon at the airport that leads the

nation in flight delays.

On board for the seven-hour trip were a three-man cockpit crew

-- Schull, First Officer Bill Duus, and Second Officer Bob Mazure -- plus

an 11-member cabin crew and 220 passengers. A typical DC-10-30 has 345

seats.

Since 1995, the jet, which has an average cruising speed of 430

mph, one engine on each wing, and a third on its tail, has had 71 service

reports, with its last major maintenance in 1997, and no accidents, records

show.

"The airplane lined up on the runway, and the captain applied

takeoff power slowly and smoothly," an NTSB report says. "At takeoff decision

speed, there was a loud explosion."

Said Tristani, the retired airline pilot: "That is the most dangerous

time for a pilot to make that decision whether to abort or to go. You have

only a hair of a second. It's the worst time."

The explosion was a catastrophic failure of the left-wing engine.

Immediately, a white "engine fail" light came on and the left-wing engine

decreased its power output by 30 percent. As the plane lifted off, fan

blades from the engine, pieces of engine covering known as cowling, and

chunks of fuselage flew off and punctured two tires as the landing gear

was raised.

Pilots in an Air Portugal plane, along with air traffic controllers,

saw something wrong.

"We had some reports, and it looks like there was some smoke.

You may have blown a couple tires on departure roll," the control tower

told the flight crew. As the DC-10 struggled to climb, the controller ordered

him to "immediately" turn right to avoid an approaching Beechjet corporate

jet.

The DC-10's left engine had become virtually useless and the right-wing

engine suddenly began to vibrate. Investigators say debris from the exploding

left-wing engine shot ahead of the plane on the runway, bounced, and was

sucked into the right-wing engine.

"Pieces were ingested by Engine #3 (right wing) causing extensive

fan blade and nose cowling damage," a Federal Aviation Administration report

says.

The last engine, the one on the jet's tail, sustained minor debris

damage, but its operation was not affected. The plane was now flying with

one engine virtually out, a second at significantly reduced power, and

a third at full power.

"Had one more engine lost a modest 30 percent of its power, that

DC-10 would be coming down, like it or not," said John King, a licensed

airline mechanic who worked for General Electric on the same engines that

the Continental plane was fitted with.

The GE engine that suffered the explosion, known as a CF6, is

one of the more common airline engines. About 5,700 are in service on planes

owned by 162 commercial airlines, according to GE.

The DC-10 could fly on its one good engine, but with it doing

so much of the work, the plane's time was limited to less than an hour,

experts said.

"When you lose two engines on a three-engine plane, you've got

problems," said Reilly, the air-traffic controller.

And there were other problems.

With two tires punctured, and the landing gear not closing completely,

a red light -- the one indicating problems with the left main landing gear

-- was lit on the cockpit panel.

As the jet struggled to climb to 3,000 feet and banked north of

Teterboro over Paterson, the NTSB report says, the crew began to "troubleshoot

the emergency" and found that when power was significantly reduced in the

right-wing engine, the vibration disappeared.

The crew, which could not be reached for comment, probably was

unaware that some of the debris that damaged the right-wing engine also

punctured the body, or fuselage, of the plane. Chunks of metal did not

penetrate the cabin, where the passengers were, but about 10 pieces did

pierce the engine cowling, the cargo hold, and left wing, reports said.

Hydraulic lines that control the brakes were cut, spraying fluid

around the plane's wheel wells.

Realizing he was in trouble, Schull requested a runway to return

quickly for an emergency landing. The crew prepared checklists for what

to do in case they lost the left- and right-wing engines entirely.

"When an emergency like that happens, everybody bends over backward

to clear airspace for them and help them out," said Dan D'Agostino, the

Newark representative to the National Air Traffic Controllers Association.

"They had problems up there. They definitely had their hands full. The

pilots did a good job."

The plane was just six miles from Newark when a piece of an engine

cover -- about 3 feet long, a foot wide, and 15 pounds -- dropped about

1,000 feet onto a Moonachie laboratory roof.

In order to land without having to brake extremely hard, the pilots

had to lighten their plane, which was carrying 120,000 pounds of fuel for

the trans-Atlantic flight. Fuel is usually dumped at 10,000 feet or higher

so it can evaporate in the sky, but Flight 60 was at 3,000 feet, and had

to land quickly, so it is possible some of the 90,000 pounds that were

jettisoned rained down on the ground.

FAA regulations state that a plane may dump fuel no lower than

2,000 feet.

But despite all the problems facing the crew, the landing was

"perfect" Reilly said.

"Everybody was extremely calm and cool," he said. "The pilot did

a real nice job handling the plane. He had some big problems, and he knew

it."

Surrounded by emergency vehicles, the plane came to rest on the

runway parallel to the one from which it had left just half an hour earlier.

Yet its problems were not quite over.

The brakes would not release, forcing the passengers to be taken

off away from a gate. The brake lines were snipped and the plane was towed

to a ramp for inspection. The debris it had left behind on the runway on

departure and on landing was collected for the investigation.

"Bringing an airplane back with two of three engines in trouble,

I don't think I'd like to be on board," C. O. Miller, a former senior investigator

for the NTSB, said after reviewing the board's report. "This was really

close to being a disaster."

The NTSB probe could take as long as six months and will end with

a probable cause based on the facts that were uncovered. The agency then

could make a recommendation on what, if any, follow-up action should be

taken by the FAA.

Staff Writer Doug Most's e-mail address is most@bergen.com

Copyright © 2000

Bergen Record Corp.

|