Families

who bought homes and established lives in Aliso Viejo, Laguna Hills, Mission

Viejo and Irvine over that time period had no idea LAXSouth was in their

future. What about the businesses who signed long-term leases in the Spectrum?

Families

who bought homes and established lives in Aliso Viejo, Laguna Hills, Mission

Viejo and Irvine over that time period had no idea LAXSouth was in their

future. What about the businesses who signed long-term leases in the Spectrum?

Printed with the permission of the OC Metro

Orange County's Business Lifestyle Magazine . July 29, 1999

The Case Against El Toro

The airport's dogfight lies beyond NIMBYism.

BY KEVIN O'LEARY

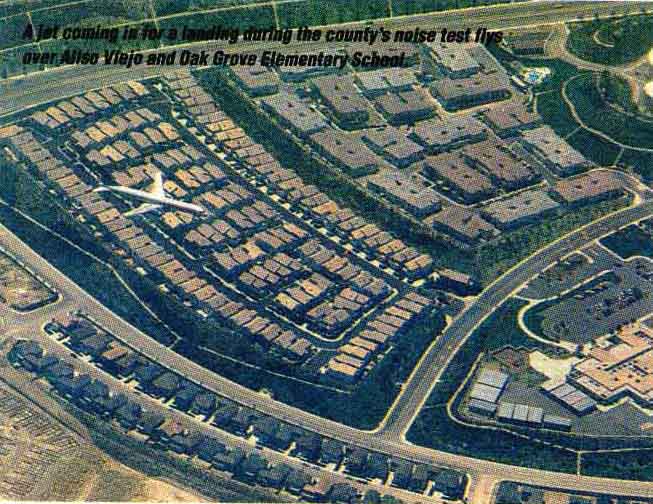

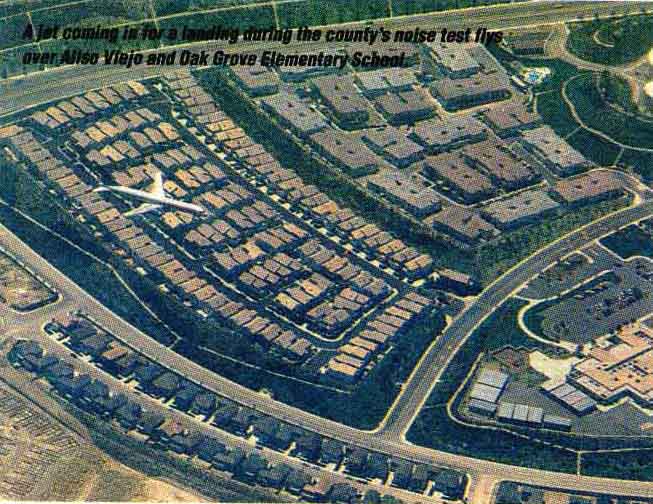

The Marines have gone south but the dogfight over the future of the World War II airstrip in the heart of South County grows more heated. It's a battle with no prisoners. One side will emerge victorious and the other will spin crashing to earth. Proponents intend on building a major international airport at the former El Toro Marine Air Station - an LAXSouth. Opponents tout the Millennium Plan, a mixture of parkland, residential construction, education facilities, light industry and high-tech.

Who will finish on top remains in doubt. North County proponents - with a majority on the county Board of Supervisors - control the planning process and are moving forward step by step. South County opponents have marshaled the resources of their cities and will file a blizzard of legal briefs to halt what they see as a blitzkrieg by powerful business interests led by former AirCal owner George Argyros.

The bitter fight recently entered a new phase. As the Marines packed their bags and the county conducted its first test of commercial jet takeoffs and landings, an American Airlines official said airline pilots associations were correct to question the safety of proposed takeoff patterns. To keep the action spinning, a powerful congressman jumped in the fray with a proposal to let a private developer decide the future of the 4,700 acres just east of the El Toro Y.

Proponents say the conversion of the Marine air base to an international airport with flights to Asia, Latin America and the East Coast is a "no brainer."

Their argument can be summarized this way: Why not make use of dual 10,000-foot and 8,000-foot runways? (These strips of concrete dwarf John Wayne's puny 5,700-foot runway and 500-acre site.) Sure, there will be noise. But each generation of Boeing aircraft is built with quieter engines. Yes, there will be traffic. But probably less than if the 4,700 acres were developed for homes.

Yes, residents in Laguna Woods, Aliso Viejo, Lake Forest, Mission Viejo and Irvine will be more affected by the airport than the North County residents of Huntington Beach, Anaheim and Brea. But the El Toro Marine Corps Air Station was zoned with a large no-home area (16,000 acres) around the runways - where the noise is loudest. El Toro is not Long Beach Airport, where the neighborhoods were built so close to the airport that residents sued successfully to radically limit flights - basically killing the airport. Proponents say the problems created by an international airport handling an estimated 28.8 million annual passengers by 2020 can be "mitigated," that the economic gains will be significant and that the opponents are simply NIMBYs (Not In My Back Yard) opposed to progress.

Opponents view themselves something like the small squad of Americans staving off German tanks in the final scene of "Saving Private Ryan." They are desperately searching for a sock bomb to blow the tires on that 747 jumbo jet lumbering down the runway.

Do opponents have rational arguments against the airport or are they just raving NIMBYs? (OC METRO detailed the proponents' difficult task in our Oct. 22, 1998 cover story, "Will El Toro Ever Fly? How mega-public projects get off the ground.") In this report, we present the best arguments of the opponents battling El Toro International - aka LAXSouth.

The Case for Opposition

1. Where is the Demand?

John Wayne Airport is busy in the early morning and early evening but during much of the day commercial flights are infrequent. In fact, many of the planes are not full. The FAA reports that JWA's "load factor," - the percentage of passengers to seats -is one of the lowest of the top 50 commercial airports in the nation.

Opponents point out that the number of people flying in and out of John Wayne Airport - with its bright new terminal and easy parking - has actually dropped over the last two years. In 1997, 7.7 million people flew from John Wayne. In 1998, the number dipped to 7.4 million and in 1999 the first six months show a continuing decline in usage. For example, in June 1998, 648,279 passengers used JWA while the number for June 1999 was 620,604.

After the morning flights have taken off, John Wayne is quiet, says Irvine City Manager Allison Hart. "You could shoot a cannon down the middle of the JWA terminal and not hit anyone," she says.

Because of noise affecting Newport Beach, the FAA, the county and the city of Newport Beach negotiated a settlement in 1985 that limits the annual number of passengers to 8.4 million until the year 2005.

Critics of El Toro, such as Irvine City Councilman Larry Agran, say the cap on passengers is a mistake. He says the cap should be on flights.

"Everything about John Wayne is anti-market. John Wayne operates at less than 50 percent of its current physical capacity - which is about 15 million annual passengers. There is enough current capacity to take care of Orange County's needs for the next 20 to 30 years.

"What about international flights? You can use John Wayne to go to Mexico and Canada. It could be designated a national airport. There have been and are nonstop flights to the New York/Newark area.

"How many people in the county fly internationally? Less than 5 percent. The people who fly internationally more than once in awhile is probably 1 percent. And those world travelers will tell you that it typically takes an hour or more to drive to an international airport."

Agran says we need a regional solution and has called on Gov. Gray

Davis to

host a regional conference on airport capacity and expansion. "Ontario

is tremen-dously underutilized," he says. In 1998, Ontario International

Airport handled 6.4 million passengers.

2. Planning Nightmare

Yes, the runways exist, but turning the El Toro Marine Corps Air Station into a modern international airport is a massive task. P&D Aviation, the county's prime consultant on aviation issues, is working on overall cost figures for El Toro International and will release them sometime in the fall, says county spokeswoman Ellen Cox Call. "There are no responsible numbers yet," says Call.

The supervisors constantly mumble the mantra of mitigating negative effects on nearby residents. Start with traffic. Large airports require skillfully planned master traffic patterns. One of the best things about the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles was the double-decking of LAX. Imagine the Los Angeles airport today without the second deck. (In 1998, 61 million passengers flew in and out of LAX.) If the planners don't get the traffic patterns right at El Toro, be ready for messy construction projects after the airport has opened.

What about the freeways that will service the airport? Today, with no airport-generated trips, the El Toro Y is a rush-hour bottleneck. The added capacity of the 73-toll road will be swept aside by an airport. Face it, say opponents, an airport that grows to nearly the size of San Francisco International - which currently handles 40 million passengers annually - is going to make traffic on the 405 and 5 freeways much worse than it is today. Adding to that freeway congestion will be the extra truck traffic carrying air freight to and from the airport. Increased cargo capacity is cited by proponents as a major reason to build El Toro International. But more trucks means more cancer-causing diesel exhaust.

"An airport doesn't exist in isolation," says David Maas, deputy director of aviation at San Jose International Airport. "It depends on a large surface transportation system. By 2010, we plan to go from 10.5 to 17 million annual passengers but to do that we will need to build double-deck roadways. It's a whole transportation system, not just runways."

What will El Toro International mean for the Irvine Spectrum - the entertainment and high-tech business zone carefully nurtured by The Irvine Co.? Can the noise of constant overhead flights be soundproofed? Can the traffic snarls be minimized? Or will some hotshot high-tech companies pull up stakes?

The planning nightmare is a dual internal and external challenge. This is not a turn-key operation. How do county planners turn an old military base into a 21st century facility? And how do they drop a major international airport into the middle of modern cutting-edge suburban high-tech Orange County without upsetting the master-planned communities and campus-environment businesses that surround the proposed airport? Opponents say the first is difficult; the second, impossible.

The city of Irvine, which is fighting the proposed airport tooth and nail, has a particular planning beef. Dan Jung, senior management analyst, says, "We are not familiar with any other city with land on a base being cut out of the LRA (Local Redevelopment Authority) process." Irvine has 440 acres within the base proper. In fact, Jung says federal guidelines about how to handle a base closure require that cities with land on the base be included in the process. The Department of Defense, Base Reuse Implementation Manual, July 1995, page C-12, reads: "The LRA should have broad-based membership, including, but not limited to, representatives from those jurisdictions with zoning authority over the property."

Agran says, "Our participation in the planning process was aborted in the case of El Toro. It makes a mockery of the general planning process that a city undertakes. Irvine is one of the most successful master-planned communities in the country. It will be eviscerated by a county determined to force an airport on us."

The former mayor says to consider this parallel: "Oh, by the way,

we want to put a nuclear waste site next to your city and we'll take a

vote statewide to get approval."

3. Bogus "Representation"

Americans believe in representative government. Opponents say they do not have representation in the case of El Toro. Unlike most metropolitan areas where one city dominates the landscape and provides the political leadership, Orange County has no single elected official who "represents" and is responsible to the entire county.

The supervisors supporting the El Toro international airport are all from North County seats. Supervisor Cynthia Coad is frank about how she believes the airport is a good idea because it will bring increased economic activity to her district. She knows none of her constituents will be calling her to complain about the thunderous roar of jets taking off. Anaheim is far enough north of the airport to get the benefits without the cost. If Coad and other pro-airport supervisors had to campaign for votes countywide they might think about the airport issue differently.

Rep. Chris Cox, R-Newport Beach, suggests solving the problem by handing the land over to a private developer. But the representation problem remains. The base is public property and the public has a major interest in how the base is developed.

A developer will make a decision based on "the highest and best use"

of the land (i.e., how much he or she can make from the land: strawberry

fields versus $400,000+ homes versus an airport versus commercial development).

But this does not address the public's right to be involved. A private

developer might be the best one to

develop the land, but only after the public decides if the area

should be an airport

or something else.

In sum, the El Toro debate points out the inadequacy of asking five county supervisors - elected by separate districts - to decide for the rest of us. Sure, some of the opposition to El Toro international is based on NIMBYism. But opponents can hurl the charge back at Supervisors Smith, Silva and Coad. Are any of them suggesting that the airport be built in their home district? Of course not. None of them would lobby for a project this mammoth and this disruptive to be plopped down in their district.

4. Straight Answers?

Part of the problem with the airport proposal is the sense that proponents are coy with the facts. At times, county officials and their allies appear to be "pulling a Clinton" - playing games with the truth. Three questions, in particular, need the Honest Abe treatment - runway strength, the future of John Wayne Airport and takeoff patterns, (in particular to the north to Loma Ridge and west toward the heart of Irvine). The controversy over takeoff patterns is complex enough to merit a separate story. See "The West Runway" in this report.

First, are the current runways adequate for the weight of commercial jumbo jets? Yes, the runways are long but they were designed for military fighters, not 747s. Are the runways and taxiways thick enough to bear the weight of big international airplanes? Either they bear the weight or the original argument for the airport - that a commercial airport can just take over the military base - is out the window. It is important to note that while El Toro occasionally handled C-130 transports, it was never a Strategic Air Command (SAC) base that handles B-52s. Instead, it was basically a fighter base. Simple question: What are the weight capabilities of the taxiways, ramps and runways?

At San Jose International, which handles 10.5 million passengers a year and offers flights to Asia and Europe, the runways are "roughly three-four foot feet thick with the top 18 inches being concrete," says Maas. Taxiways and ramps are a similar thickness to handle widebody L-1011s, DC-10s, MD-11s as well as the new Boeing 777s and 747s, he says.

P & D Aviation reports that at El Toro, the "pavement surface thickness (asphalt and concrete) ranges from six to 15 inches on runways; three to 13 inches on taxiways and eight to 13 inches on ramps...while a fully loaded 747 could be accommodated on an infrequent basis, in the interest of extending the useful life of airfield pavements, a pavement rehabilitation program is assumed in the planning."

Next, how does John Wayne Airport fit into the equation of an El Toro Airport? John Wayne has a lovely terminal building and is currently adding more parking. But the airport is limited. The runways are short and therefore the largest commercial aircraft cannot use the airport. Most travelers who want to fly nonstop to the east coast and all passengers flying to Asia or Europe must go to LAX. In addition, most of the county's air cargo must be trucked to LAX or Ontario.

Originally, the county proposed maintaining John Wayne Airport for medium range domestic trips and having El Toro international focus on long range flights and air cargo. The two airports were to be linked by a "people mover" system and El Toro was to be limited to approximately 23.4 million annual passengers (m.a.p.) with John Wayne handling 10.1 million passengers by 2020. But later county planners said the monorail system would be too costly. In March 1999, the supervisors abandoned the idea of linking the two airports together and increased the proposed size of El Toro International to 28.8 million passengers a year by 2020 and dropped John Wayne's size to 5.4 million annual passengers.

Does the new scenario mean that John Wayne Airport will eventually be seen as redundant and either be closed or severely scaled back?

* Originally, the county was proposing a medium-sized El Toro International doing cargo/international flights in tandem with John Wayne staying at 8-10 million domestic passengers. A medium-sized El Toro would be comparable to San Jose International, which handles jumbo jets flying directly to Japan and Europe.

*Now, it looks as if the real choice is a slight increase of passengers at John Wayne (8-12 m.a.p.) or a mega-El Toro International (28+ m.a.p.). Both the Airline Pilots Association and one of the major airlines, American Airlines, are on record saying the county should choose one or the other.

Kevin O'Connor is a relative newcomer to Orange County. A native of Boston, he moved to Southern California three years ago to take an engineering job at Eaton Corp. Kevin, his wife, Laurie, and their two children live in Irvine in University Park where their house backs up to a wide green belt filled with eucalyptus trees. O'Connor says, "Going from John Wayne to a major international airport is a big step. It will change the community. It will change the county. Anyone who doesn't recognize that is naive."

Defining O.C.

El Toro international is problematic for many reasons. At bottom, it can be argued that the project is 15 to 20 years too late. Twenty years ago, adjustments could have been made. Development in the area of the El Toro Y was much less dense. "Back in 1980, there were literally more cows than people in Orange County," says Dave Ellis, a pro-airport spokesman.

Since 1980, a great deal of development and construction has taken

place in the adjoining communities.  Families

who bought homes and established lives in Aliso Viejo, Laguna Hills, Mission

Viejo and Irvine over that time period had no idea LAXSouth was in their

future. What about the businesses who signed long-term leases in the Spectrum?

Families

who bought homes and established lives in Aliso Viejo, Laguna Hills, Mission

Viejo and Irvine over that time period had no idea LAXSouth was in their

future. What about the businesses who signed long-term leases in the Spectrum?

How the issue is decided will in large measure define the future of Orange County. A major airport would boost economic growth, but at what cost? Are there alternative uses for the 4,700 acres that boost economic growth even more? Opponents of El Toro International certainly think so.

Thus far, Orange County has been about a balance between economic energy and a high quality of life. People who want to be in the absolute center of economic life gravitate to New York and the Silicon Valley. Like Hollywood and Washington, D.C. - these are very much company towns. Conversation about "the business" never stops.

By contrast, in Orange County, people can find variety. High-flying Broadcom could be based in the Silicon Valley but founders Henry Nicholas III and Henry Samueli decided to move from Westwood to Orange County instead. The reason, in part, says wife Stacey Nicholas, was because life is more balanced in Orange County.

As the battle over El Toro enters a new phase, the challenge for opponents is to convince the public that they have a plan for the base that will maintain Orange County's vaunted quality of life while generating as much - or more - economic punch as an El Toro international.

In this spirit, we make a modest suggestion. See "Stanford South" on the following page. OCM